Wearable devices, such as smartwatches, could be used to detect an increased risk of developing heart failure and irregular heart rhythms in adulthood, according to a new study led by researchers at UCL (University College London) and involving I3A-Unizar researcher Julia Ramírez.

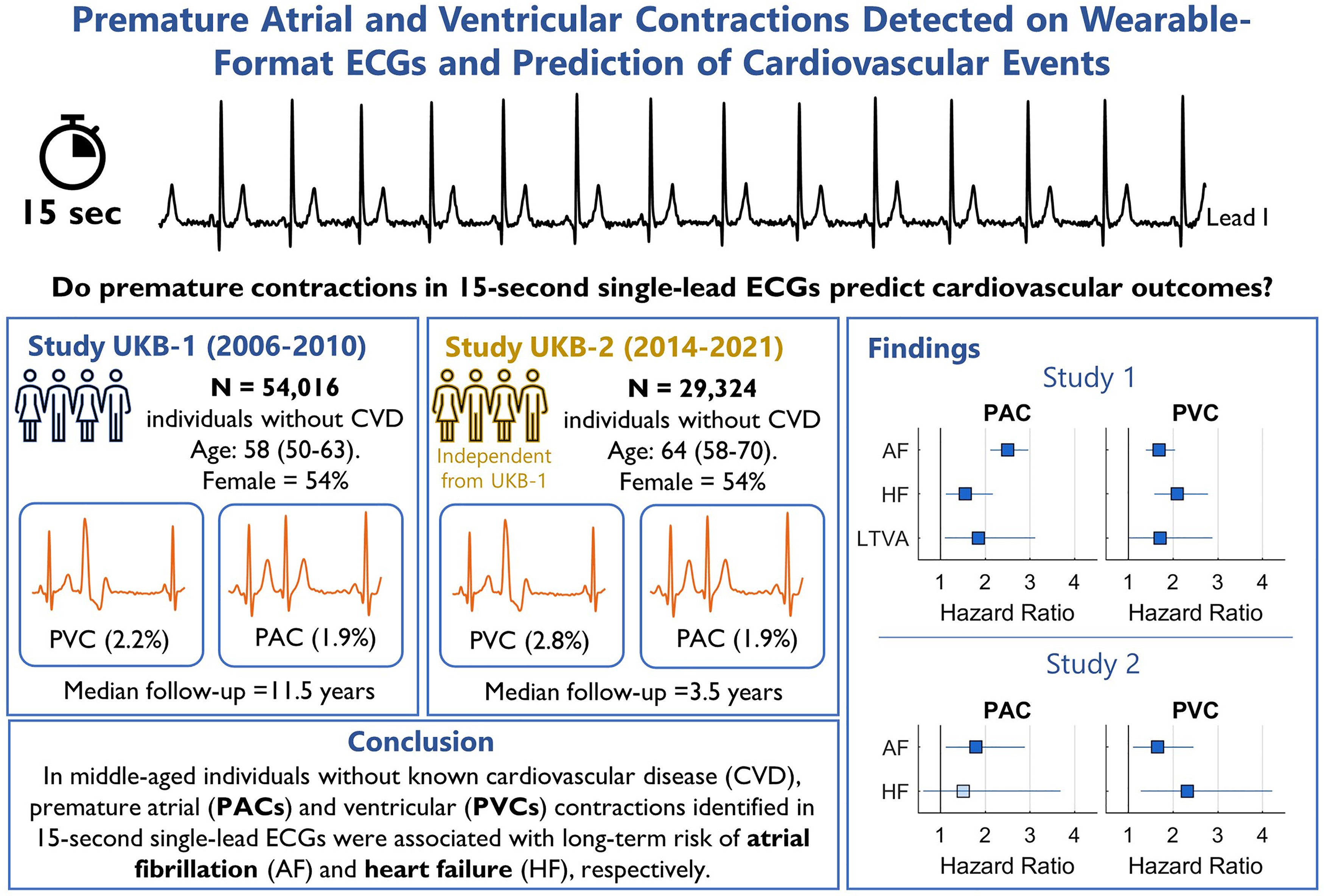

Wearable devices are making the electrocardiogram (ECG) a ubiquitous medical test. This study assesses the association between premature ventricular and atrial contractions detected on the ECG (only with information collected for 15 seconds) and the risk of future cardiovascular events.

The scientific paper, recently published in The European Heart Journal - Digital Health, shows premature atrial and ventricular contractions detected on electrocardiograms obtained with portable devices and the prediction of cardiovascular events.

The ECG records analysed were from people aged 50-70 years with no known cardiovascular disease at the time. In middle-aged people, premature contractions identified on the ECG are strongly associated with an increased risk of developing atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure (HF) in the next 10 years.

The peer-reviewed study analysed data from 83,000 people who had undergone a 15-second electrocardiogram comparable to those taken with smartwatches or mobile apps.

The researchers developed algorithms to detect premature heartbeats, which are usually benign, but if they occur frequently, they are associated with conditions such as heart failure and arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat).

They found that of the people who took part in the recording, one in 50 had a premature heartbeat and that this was associated with an increased risk of developing heart failure or atrial fibrillation over the next 10 years of around 100%.

Heart failure occurs when the heart weakens. It is often untreatable. Atrial fibrillation occurs when abnormal electrical impulses suddenly start firing in the upper chambers of the heart (atria), causing an irregular and often abnormally fast heart rate. It can be life-limiting as it can cause dizziness, shortness of breath and tiredness. It is associated with a five-fold increased risk of stroke.

The lead author of the paper, Dr Michele Orini of the UCL Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, who did his PhD thesis at the I3A, says that this study "suggests that ECGs from wearable devices can help detect and prevent future heart disease", so the next step is to "investigate how detection in people using wearable devices might work better in practice".

This could be combined with the use of artificial intelligence and other computational tools "to quickly identify ECGs that indicate a higher risk, as we did in our study, leading to a more accurate assessment of risk in the population and helping to reduce the burden of these diseases," Dr Orini notes.

If people at risk of heart failure and arrhythmia can be identified at an early stage, "we could assess higher-risk patients more effectively and help prevent them by starting treatment early and providing lifestyle advice on the importance of regular and moderate exercise and diet," says Julia Ramirez, I3A researcher and co-author of the paper.

Detecting electrical signals in mobile devices

An ECG uses sensors attached to the skin to detect the electrical signals produced by the heart each time it beats. In clinical settings, several sensors are placed around the body and a medical specialist watches the recordings for signs of a potential problem. Consumer wearable devices use sensors integrated into a single device and, as a result, are less cumbersome but may be less accurate.

Cómo se ha trabajado

In this study, the research team used machine learning and an automated computer tool to identify recordings with premature beats. These beats were classified as premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), which come from the lower chambers of the heart, or premature atrial contractions (PACs), which come from the upper chambers. Recordings identified as having premature beats and some recordings that were not considered to have such premature beats were reviewed by two experts to ensure that the classification was correct.

The researchers first analysed data from 54,016 participants in the UK Biobank project with a median age of 58, whose health was followed for an average of 11.5 years after their ECG was recorded. They then looked at a second group of 29,324 participants, with a median age of 64, who were followed for 3.5 years.

After adjusting for risk factors such as age and medication use, the researchers found that a premature beating of the lower chambers of the heart was associated with a two-fold increase in subsequent heart failure, while premature beating of the upper chambers (atria) was associated with a two-fold increase in cases of atrial fibrillation.

The study involved researchers from the UCL Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, the UCL MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing, the Barts He art Centre (Barts Health NHS Trust), Queen Mary University of London and the Aragon Institute for Engineering Research (I3A) at the University of Zaragoza. It was supported by the Medical Research Council and the British Heart Foundation, as well as the NIHR Barts Biomedical Research Centre.

Link to the full article: Full paper in The European Heart Journal - Digital Health

Related article: “Las variaciones morfológicas de la onda T del ECG predicen el riesgo de arritmia ventricular en poblaciones de riesgo bajo y moderado”. Ramírez J. et al, Journal of the American Heart Association.